Clearly Cairene graffiti has lost momentum during this year. Having been the faithful barometer of the revolution over the past three years, graffiti has recently faced transmutations and drawbacks that run parallel with the political process of restoring “order” in the street. The heartbreaking story of the recent death of a cheerful and bright young graffiti artist, nineteen-year-old Hisham Rizq, completes this sad picture. He had disappeared a week before his corpse was discovered in the morgue of Zeinhom in Cairo in late June 2014. The official cause of his death, provided by the government, was that he drowned in the Nile. The story was hardly believable. In today´s Egypt, some forty thousand people remain incarcerated in prisons, while many others are reported to have died in police stations of heart failure, crammed in confined spaces in the unbearable summer heat. Rizq, it was speculated, was probably arrested while protesting and consequently killed by the security forces.

What makes the story even more depressing is that Rizq was a dedicated activist of the April 6 Youth Movement, one of the main catalysts of the January 25 Revolution. Rizq was equally active in various other political organizations, as well as in the Association of Revolutionary Artists (Rabitat Fanani al-Thawra) who continued to contribute to the graffiti scene in Cairo. He was not only celebrated as a street artist, but was equally well known as a participant in numerous demonstrations. For example, he was recently seen protesting against the government after General Sisi became president.

In fact, Rizq was not the first young man barely twenty years of age to be killed by the security forces in the past three and a half years. Evidently, a particular group of bright young women and men has become the target of the regime. However, for the circle of graffiti artists, Rizq´s death marked a dramatic turn, signalling the danger of street politics under military rule, perhaps even marking the end of street art, after such a mesmerizing blossoming over three years since the January 25 Revolution began. A memorial celebration was held in Abdin Square, another public space that turned into an outdoor art hub known as Al-Fann Midan (Art is a Square) festival for the past two years. A Ramadan iftar banquet was also organized in memory of Rizq the “martyr” on Youssef al-Guindi Street, which cuts across the iconic Mohamed Mahmoud Street. Finally, a huge portrait was recently painted by his friend, graffiti artist Ammar Abu Bakr on Mohamed Mahmoud Street itself. This street had witnessed the most violent incidents in 2011 and 2012, leading to numerous killings and the wounding of thousands, and had also turned into a “memorial space” (see Abaza, Jadaliyya, 10 March 2012, 12 June, 2012, 25 January 2013, 30 June 2013).

[The wall of Mohammed Mahmoud Street, a few meters from the entrance of the gate of the American University in Cairo. A poor child, (most probably a street child) eating a falafel sandwich. Captured 25 November 2013]

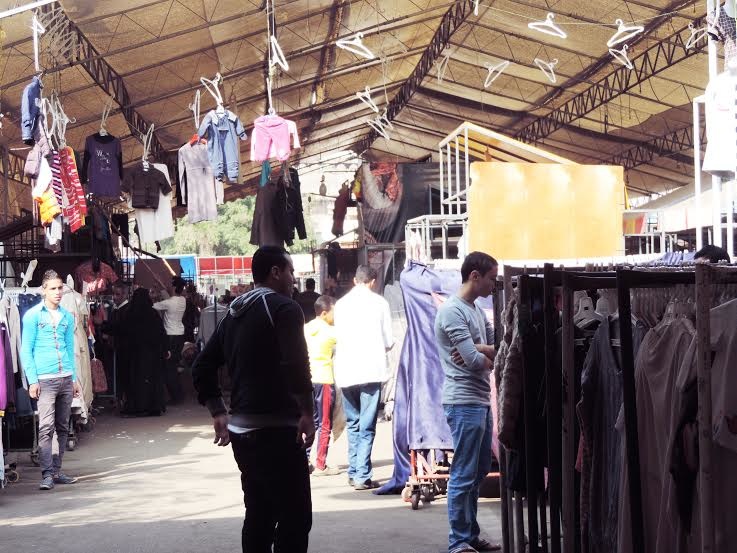

Rizq´s death coincides with the Sisi regime´s massive campaign to “clean up” Downtown Cairo, by closing down some cafés and forcefully evicting street vendors, who constitute some five million people surviving within the informal sector, accounting for thirty percent of the total economy according to Ahram Online. These vendors were recently relocated to a confined area near a bus station in the Turguman quarter. This decision to remove the street vendors was welcomed in various circles since it did visually relieve the centre congestion and eased the flow of traffic. Downtown Cairo does indeed look calmer and more orderly now. However, several architects and critics pointed out that this was purely a superficial aesthetic move, since no long term, realistic solution has been proposed for the millions of jobless in Egypt’s streets. This was the argument of architect Omar Nagati, who has worked closely with the newly founded Syndicate of Street Vendors, though he acknowledges that the community of street vendors is infiltrated by mafia elements.

[Reallocated Downtown Street Vendors in al-Sahaafa Street. Captured November 2014]

With the exception of the recent portrait of Rizq drawn by Ammar Abu Bakr, it is no coincidence that the centre of Cairo has witnessed a massive whitewash of its walls, together with a destruction of graffiti. However, the walls of Mohamed Mahmoud Street had hardly changed since last November 2013, with the exception of Rizq´s portrait. Unlike in previous years, their whitewashing has not been counteracted with ironic, irreverent new paintings. Dare one say that the last portrait of Rizq (picture1), marks the tragic end of an era in Egyptian street art? Is there a collective sentiment of exhaustion, and fear of violent police retaliation? Or is it that the repetitive portraiture of martyrs in the city, their growth in size as time went by, has lost the powerful effect it produced at the start of the revolution? Also, is there a relationship between the decline of the graffiti in Mohammed Mahmoud Street and the most recent graffiti in downtown Cairo, which seems to be turning into a sort of decorative art, whose political messages are increasingly blurred? For example, groups of students from the Faculty of Fine Arts are now often seen painting the stairs of bridges and coloring the walls in poor, popular quarters. Is this going to replace graffiti to become the next most admired endeavour in Egyptian urban life, perhaps precisely because it is rather depoliticised compared to graffiti? And how can we interpret the article in Ahram Online, published a year ago by Chahinaz Gheith, differentiating between the graffiti of 2011 and the most recent words written on walls that she describes as “abusive,” a form of a “visual pollution,” a “war of words,” and “obscenities,” including sectarian statements like “all Copts are bastards”?

[Cropped adjusted Panorama of Mohammed Mahmoud Street. Caption: Panorama of Mohammed Mahmoud Street. Captured 22 February 2013]

These speculations should be addressed in relation to one major issue, not necessarily restricted to street art, but rather, how long can street mobilization through protests endure after so many killings, disfigurations, mutilations, and sufferings that have gone without restoring justice?

Egypt appears to be experiencing a collective trauma, if not an insurmountable malaise, in which denunciation and witch-hunting are becoming quite familiar. There is a growing exodus of human rights activists, artists, intellectuals, and political activists, who feel personally threatened by the new regime in Egypt. Earlier this year, singer-songwriter Ramy Essam, who became famous in Tahrir Square, moved to Sweden, citing the mass arrests and censorship as his reason. In May 2014, the much celebrated graffiti artist Ganzeer left the country for the United States, fearing for his life after that he underwent a defamation campaign on national television. In a recent interview, Ganzeer explains the gravity of the situation as follows:

“As street artists, I think we are less targeted than others who might be affiliated, but at the same time, it is not like it is an entirely safe thing either; you know you take risky actions, and it has been risky since the first day. Maybe now it is only far riskier because it is very obvious that the police have been given carte blanche to take any means necessary to ensure security—or, at least Sisi’s security—and so that means there is more of an inclination from their side to keep an eye out for street artists more strictly than before, or slap accusations or crimes on them that may not be true.”

Particularly concerning has been the recent issuing of a draconian law curtailing the activities of NGOs and human rights organizations. A large number of young activists, including leaders of the 6th April Youth Movement who protested against this protest law, have been arrested. There was even the recent brief arrest in Cairo of the well-known French journalist Alain Gresh, chief editor of Le Monde Diplomatique. He was discussing current events in a café with two Egyptian women, and was publicly denounced by a woman at another table, before being questioned by police. This collective feeling of being personally targeted, while the circle of one´s acquaintance contracts day after day, is what Basma Abdel Aziz warns of in her recent article in Al-Shorouk newspaper. The feeling of being threatened is not only targeting those who are politically active, it is extending to include those who remained silent by refusing to join the pervasive state propaganda machinery. Thus, as Abdel Aziz has argued, many raise the question: when would it be the right time to depart for good?

The authorities’ decision to conduct a relentless “war on terror”, as retaliation for the escalating terrorist attacks against the army, has certainly contributed to a collective feeling of angst. So too have the actual attacks, whereby numerous Egyptian soldiers on both the Eastern and Western borders have not merely been killed but many beheaded, indicating that the so-called Islamic State organization, and/or its identified supporters, have reached the country. Dare one say that with the pervasive media propaganda, popular sentiments have shifted towards the opinion that the respect of human rights and the right to protest remain secondary with regard to the greater cause of national security threats? This might explain the more conservative artistic campaigns of the Fine Arts students, while the rage of some of the marginalized, or the sectarian, political players in Egypt might tell us more about the less savory wall statements.

As Sherief Gaber argued in a recent presentation at the American University in Cairo, for those who still maintain faith in the revolutionary path, the decisive struggle revolves today around ‘political memory’, given the pervasive smearing campaigns against activists and human rights advocates. The battle over recording and archiving for an alternative narrative of what truly happened during the past three years is becoming a paramount endeavor to counteract the current invasive propaganda machinery.

Of course, there are many pessimists who believe that the “restoration” of the ancien regime has already taken place, epitomized in the acquittal of Mubarak and his cronies, together with the fierce comeback of the internal security apparatus. Having said that, the problem remains. Who killed the protesters during the first days of the January 2011 uprisings? Who is accountable for the carnage of the night of the “battle of the camel” on Tahrir Square in February 2011? Furthermore, the longue durée, complex and unpredictable processes of insurrections compel us to raise the question: what sort of alternative forms of struggle should one adopt under military rule? Considering this moment of perilous street politics, how should the struggle for change look? How can the emerging political parties, civil society actors and cultural workers survive under the recent anti-terrorist and NGO´s laws curtailing freedoms?

I end this piece with my starting point, with Hisham Rizk, to argue that it was not a coincidence that his death was once more a warning sign, instigating departures together with sentiments of defeat. From day one protesters have been systematically confronted with killings and violence, and a number of activists and observers have been reflecting on whether to adopt passive or violent strategies in resistance. And violence continues to persist. One day before the commemoration of the fourth anniversary of the revolution, a young and beautiful activist, Shaimaa El Sabagh, member of Socialist Popular Alliance Party, was shot dead by police forces in Downtown Cairo while she was participating in a march. She died while carrying flowers, to be deposited for the martyrs of the revolution in Tahrir Square. The excessive cost involved in street politics is primarily being paid by young men and women like Shaimaa, or like Alaa Abdel Fattah, Ahmed Douma, Yara Sallam, and Sanaa Seif, along with many more who remain nameless, who have been sent to prison for several years for daring to protest against the regime. If short term perspectives seem to be deadlocked in pessimism, long term visionary speculations cannot afford to be.

A series of forthcoming articles will attempt to reflect on both the external and internal paradoxes and struggles for recognition continuing within the field of street art in Egypt today. They will interweave these with the powerful external factor of the commodification of revolutionary art, which calls for further research into Cairene urban life in the context of the incompleteness of the revolution.